Mur Bonifacien Pierre Seche Tramizi Chemin Campagne Bonifacio

Mur Bonifacien Pierre Seche Tramizi Chemin Campagne BonifacioTame the countryside

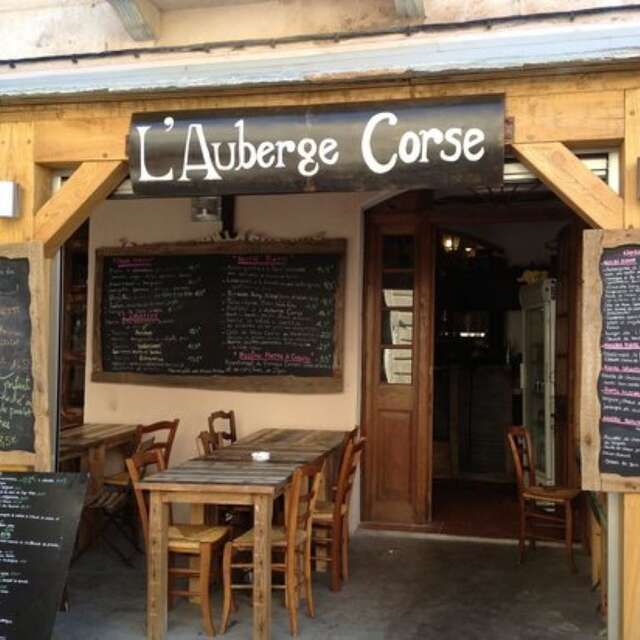

If you’ve spent even an hour in the upper town, you’ll have noticed that the buildings are centuries old. Imagine, then, that the people who lived in Bonifacio in those days were surrounded by nothing but luxuriant nature, sometimes welcoming, sometimes difficult to get to grips with on a daily basis. So the people of Bonifacio tried to tame it, to make the most of what it had to offer. They planted gardens, built paths, low walls and shelters. Bonifacio’s rural landscapes tell the story of the peasants who shaped the town and its way of life.